Americans rooting for wider adoption of ranked choice voting (RCV) across the US were let down in early November when Massachusetts voters soundly defeated a ballot initiative to implement it statewide. Hope was restored two weeks later, though, when a similar initiative finally eked out a win in Alaska. But the loss in Massachusetts was a discouraging moment for RCV campaigns in Florida, Texas, Colorado, and elsewhere.

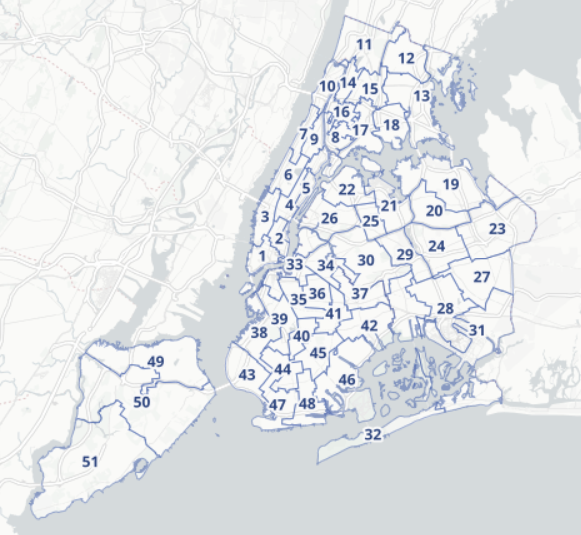

Aversion to more bad news raises the stakes for the introduction of RCV in New York City’s municipal elections next year. A shaky rollout there would embolden RCV opponents who argue that the system is too complicated and not worth the trouble.

On the other hand, a smooth rollout in New York would restore RCV’s political momentum. If voters there are reasonably happy in the end (with not just the process, but also the outcome), the more people outside New York can feel confident that the system makes sense. Models of success make springboards for more.

The New York’s upgrade will be the largest RCV election ever held in the US… the 2nd largest in the world after Australia’s.

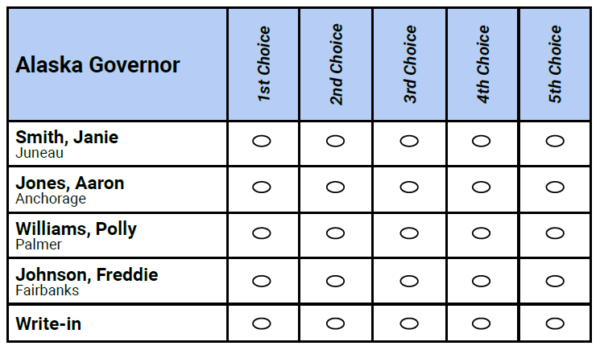

Switching ballot systems isn’t trivial… certainly not at New York City scale. Few voters there have ever seen the Top-5 grid design that’s been selected for their elections. Even fewer have heard of the instant runoff algorithm that will be used to tabulate results. And, since those new grids gobble up so much space on paper, election workers who’ve already had to step up for the pandemic will now have to shoulder the additional logistical burdens of long, multi-page ballots.

The good news is that the largest recent implementation of RCV… Maine’s in 2018… has gone well. So have smaller rollouts in municipalities across Massachusetts and California. Experience adds comfort.

RCV’s record of success isn’t surprising. To the extent that voting machine makers know a growing market when they see one, incentives for smooth rollouts will drive virtuous cycles of innovation and competition. And, despite perennial warnings by naysayers about too much complexity, it turns out that the concept of ranking likes up and dislikes down is easily understood… especially for an American public steeped in reality show voting, “peoples choice” awards, and sports scores galore. The logic of runoff arithmetic and how it advances democratic principles is easily mastered as well, especially when compared to the arcane rules of the Electoral College.

Still, voters in America’s biggest city are in store for a novel experience. They’ll be piloting a relatively new model for fulfilling the chores of democratic citizenship, but at a scale never seen before, with an audience of millions. Stumbles in that fishbowl won’t be fun. Each little trip-up, no matter how inconsequential, will be taken as grist for the mills of people who wish RCV to fail. Fortunately, in preparing ground for their own success, communities such as Minneapolis, Minnesota and Benton, Washington left a body of video explainers that newcomers elsewhere can use to ease their way up the learning curve.

New Yorkers (and anyone else who’s interested) will get a sense of what to expect through RadioLab’s coverage of the latest RCV Mayoral election in San Francisco. But Curt Merlo’s artwork for the program (shown above) doesn’t ignore the risks of heedless ambition: Reengineering can go painfully wrong if its focus becomes too narrow.

RCV’s biggest fans are counting on it to transform America’s political culture. They believe it can eliminate one of the most annoying flaws of our current system… its baked-in inability to handle multi-party elections fairly.

In typical elections across the US, when more than two candidates run for the same office, the third and fourth choice alternatives often wind up playing the role of vote-siphoning, coalition-facturing “spoilers.” In other words, our system renders multi-candidate races vulnerable to bizarre upsets and broadly-disappointing outcomes. RCV solves that problem, freeing voters to support any candidate, no matter how minor, while assuring they won’t lose their opportunity to have a say on the final outcome. It puts voters in position to express themselves more fully, more honestly, and more realistically.

Another debilitating flaw of our current primary process is that many states deny independent voters the right to participate. Shutting out so many centrist and moderate voices at that critical early stage gives an automatic advantage to base-baiters who appeal from the tips of their party’s wings.

Thus, our general elections have become increasingly mired in partisan antipathy. Mud flies. Brawls ensue. Paths to constructive collaboration are closed off.

The cause of common cause among politicians provides little ground for champions. The proverbial aisle has become a perilous gulf. Those who dare to cross it face career-killing ostracism.

Giving an inside track to candidates who lack broad general appeal explains why so many win. Some states have determined to address that defect systematically, replacing closed primaries with non-partisan open ones. Washington and California have done this, but a like-minded measure in Florida just failed, garnering 57 percent of the vote, but needing 60.

The principle of an open primary is that every citizen should be able to weigh in on who will face off in the general election… not just registered members of established political parties. The approach essentially overhauls the rules of ballot access. General elections would no longer be races between party nominees, but between the strongest candidates the initial field can muster.

Open primary and RCV systems aren’t identical, but their promises are compatible. Both are intended to promote the ascension of heretofore technically-excluded, pragmatically-minded problem solvers. And, by elevating those centrists, both approaches present an opportunity to transform our political landscape.

Some skeptics may consider the effort to enact such fundamental kinds of election reform to be a useless risk, openly doubting whether its benefits could ever be fulfilled as advertised.

Others — quite a few others — will oppose it because they object to what would happen if it does work. For example, heavy consumers of cable news, talk radio, and social media who enjoy bingeing on partisan outrage and anger will probably say “meh” as political discourse cools down into blandness. And businesses which currently depend on exploiting that outrage would probably consider the shift in tone to be an alarming threat against their revenue model.

More importantly, having lost the attention-stealing advantages that our fire-breathing two-party culture had bestowed on them, many politicians will have to reconsider what it means to seek office. Campaigns that run from a single, base-baiting partisan leg would no longer find that stance so easy and inviting. Going forward in this remade world, the ability to establish broader footing will confer advantage.

It’s increasingly obvious that slipping the mathematical shackles of the D/R duopoly looks like America’s best chance to free itself from chronic divisiveness. Most would welcome just that escape by itself, but RCV can also deliver remedy and relief. It’s been associated with surprisingly civil political debates and more than a few eruptions of issue-focused, coalitional campaigning. For Americans craving an antidote to our long plague of hyper-partisanship, RCV may be the answer.

Enterprising New Yorkers are already working to get ahead of the cultural shift, or at least ride it well. The group 21 In ’21 kicked things off by using RCV to pick its slate of candidates for the City Council races. Though its overarching concern is women’s representation in city leadership, the movement sets the stage for other kinds of coalitional conversations.

Issue-oriented slate building of this sort can lead to the holy grail of what’s been called the “citizens agenda” model of political campaigns. According to NYU Journalism Professor Jay Rosen, “It revolves around the power of a single question: ‘What do you want the candidates to be discussing as they compete for votes?'”

Next year’s primary will put a spotlight on the question of whether RCV really can illuminate a better path for democracy. For the time being, however, the key challenge in New York will be ensuring that its election board ramps up properly and puts its voters in good position to step up on election day.